Henry Ford, Henry Leland, Billy

Durant and the other winners of the competition to build a successful car

company are huge figures, but in their way, they’re freaks. They succeeded

where almost no one else did. In HCC #88, we featured a St. Louis

automobile, from one of about 100 car companies based there. How many are there

today? For several years, I’ve been mapping the locations of America’s car

factories and if you look at Detroit, you see layer upon layer of failure—an

E.M.F. plant will be in an old Briggs Detroiter factory, which Studebaker then

sold to REO, then acquired by Willys and later used to stamp Chrysler Imperial

bodies. Henry Ford II’s Renaissance Center became GM’s white elephant and has

under its foundations the factories of half-a-dozen makes. Pick the nearest

town of 20,000 or more people—odds are that someone built a car there. Of the

hundreds of makes started in England, the largest surviving English-owned car

company is Morgan, a manufacturer that doesn’t build 1,000 cars in a year.

Failure wasn’t expected a century

ago; after all, investors threw millions of dollars at manufacturers. But no

one was surprised when a company went under, as that’s what practically all of

them did. Often a carmaker would only build a few weird prototypes or, at best,

a year or two of production. Often as not, the promoters, managers, financiers

and engineers would pop up again later that year under a new name with their

next big idea, and try again. For an early automotive pioneer, failure was

always an option.

That isn’t to say people expected

to fail; aside from a few scam artists, everyone had some plan. But inside,

somewhere, many must have known that their chances were slim. Did William Mazzei

really think his amphibious Hydromotor was the next big thing? Was

Fageol actually going to sell a Hall-Scott aero-engined car for $17,000?

Neither did, yet many persevered and the result was a culture of innovation and

experimentation the likes of which America hasn’t seen again outside Silicon

Valley.

When you’re willing to fail, there

are no limits to what you can consider, and the products of the era before the

Depression reflect this: Rotating reciprocating engines? Adams-Farwell gave it

a shot. Driving the front wheels directly by the crankshaft? Walter Christie

raced ’em that way. Engines burned oil, kerosene, alcohol, coal gas, and

anything else you could light on fire or make explode. Knight’s valveless,

Itala’s rotary valve and Franklin’s valve-and-a-half engines all ran. In

hindsight some were obviously doomed, but a crazy idea and a great idea can

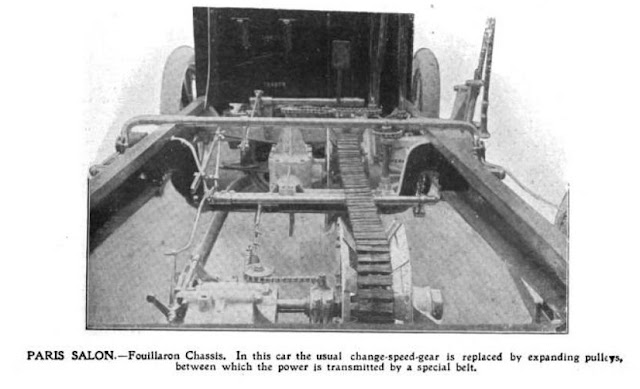

both look good when they first appear. This spirit also yielded Pilain’s 1911

internally expanding hydraulic front-wheel brakes, Levassor’s 1903 mechanical

fuel injection, Fouillaron’s continuously variable belt drive (and diagonal

engine) and Owen Magnetic’s electromagnetic automatic. Those were just as odd

in their day as B-L-M’s (of Brooklyn) cast-iron clutch facing or

Wilson-Pilcher’s engine pivots. Then again, the ’04 Wilson-Picher’s engines

were horizontally opposed 2.7-liter fours and 4.0-liter sixes (with a four

speed), arrangements that Porsche fans favor a century later.

Today, not only every car but also their every option must succeed. Without accepting failure, you can’t have true originality. As a result, we’ve suffered through a generation of tepid, similar cars, where the distinguishing features are now infotainment systems. The capacity for creativity hasn’t been lost; that’s obvious from the responses to Federal demands for higher fuel economy we’re seeing, such as amazingly efficient turbo four- and six-cylinder engines producing V-8 power, the

transmissions behind them and battery-assist drivetrains. But these are reactions—they’re fixing a problem, not speculating about the future.

I'm not sure we should subsidize failure, but there has

to be room for it. Engineers and designers have to be not only encouraged to

take risks, but executives need to bring them to market knowing they’ll get

another chance. When money people run car companies, the results are

disastrous, as Bob Nardelli’s time at Chrysler illustrated. Inventors know that

there’s no straight path to success, and sometimes it’s the losers that take us

to the most interesting places.